Morphing Through Time!

Out of the ashes of gloom and despair, our mammalian ancestors managed to emerge riding the surf of survival, birthing forth an exquisite diversity, precedence of which remains to be seen on other water worlds in orbit around our mighty Sun.

In this vast cosmos, we are a curious anomaly. Stuck in the maze of time, we carry the remains of long-lost ancestors within every growing wrinkle of the skin, colourful tendrils of the iris, within every involuntary reflex and twitch of our muscles and within every cell of the body. From the day we’re born, we begin an intimate whisper chat with curiosity. A trait we never asked for – but which keeps a persisting presence in our specie. Natural selection seems to have carefully crafted this appeal. How many times have we spent more than a couple of seconds looking at the beauty of the sunset, or the myriad of colourful stars at night – bright and dim? Curiosity has a mind of its own. Our ancient forefathers dwelled on their ability to outsmart and outlive predators; a process that has ensured our existence and survival. Driven by this mysterious force within, I wonder how many of them looked up at the night sky and wondered in a language long lost to the fog of epochs, “are we alone?”, and “why are we here?” – an everlasting itch. Where we’ve heaped functional structures by virtue of our slow crawl through the temple of time, we’ve also gathered the moss of vestigial features, a relic from the past that continues to live in our present.

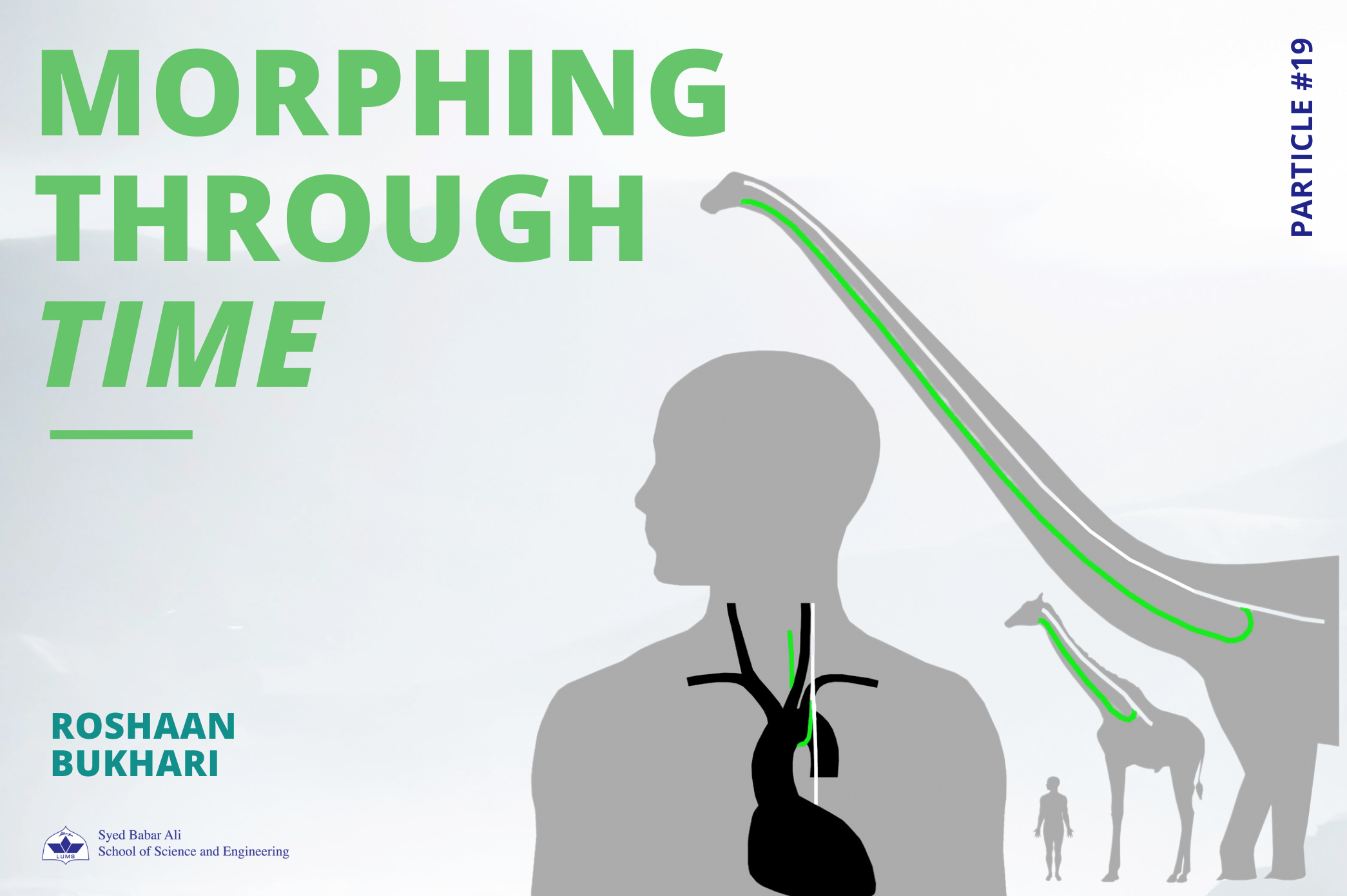

Some interesting examples include the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, whose path in the body seems inane, and completely non-intuitive. These sets of nerves originate from the brain and innervate the larynx (voice box). Whereas the right recurrent laryngeal nerve takes a more direct path from the brain to the voice box, just rounding the corner near one of the carotid arteries in the next, the left counterpart first travels all the way down through the neck, into the thorax, winding neatly around the arch of aorta, the largest blood carrying vessel exiting the heart, then making its way back up the thorax, into the neck and finally terminating at its destination, the larynx. In this drawn-out course, it does not seem to innervate anything else, as if the entire round trip around the aorta was just a waste of precious nervous tissue, something the body relies much on transmitting tiny electrical signals to power up its entire suite of physiological processes.

So, what is it?

A mindless meandering or is there a method to this madness? It turns out that the answer lies at the tail end of a much deeper look into our past. Since the Earth is mostly water, the earlier life forms were almost entirely water borne. Fish, and other marine life had uncomplicated paths of innervation from the brain to their gills. This network of innervation included the prelude to what are now the recurrent laryngeal nerves, found in all mammals. As evolution proceeded, organisms got larger, the heart moved lower into the thorax and ‘dragged’ one of the nerves down with it, hooking around what was to become the arch of aorta. This effect is most pronounced in the giraffe, which on average has a neck that is at least six feet long, and the left recurrent laryngeal nerve travels this entire course, only to innervate the larynx present in the upper part of the neck.

The gift of evolution keeps on giving. There is a mighty surprise hiding in the wrists of 14% of the population. Lay your arm on a flat surface and try to join your thumb with your pinky finger. Do you see a conspicuous tendon rise above the epithelial landscape right in the middle of the wrist? If you don’t, then natural selection has put you in a rare 14% of the population, that is devoid of a muscle in the wrist called the palmaris longus. The palmaris longus is undergoing what is known as non-adaptive, stochastic evolution. This means that the muscle is slowly vanishing from our bodies and is no longer in demand as primates transition from an arboreous lifestyle. However, it is still present in certain species of orangutans!

The nature of adaptation is plastic. Trillions of cells, each one a castle of sublimity, encapsulated with a delicate boundary, all functioning in a peaceful coexistence, never tired nor bored. What is the extent of this plasticity? Well, it literally goes all the way to the sun! Our eyes are two 5-millimeter-wide light buckets, programmed to create tiny electrical impulses from the gentle absorption of photons by a thin layer of retinal tissue. Our primeval ancestors had spent most of their time under natural lighting conditions i.e., the sun as their only source of bright light. Over time, their retina evolved to become most sensitive in detecting wavelengths of light that the sun showered most abundantly and generously. It is understandable how this could have been most advantageous for survival. With advances in physics, we understand that stars like the sun emit blackbody radiation that peaks in the wavelength of about 500 nanometers (Wien’s law), which is fancy for the colour green. Also, sunlight is least intense in red colour – no wonder then, that our eyes are most sensitive to green and least to red! In fact, the emission spectrum of the sun mostly fits neatly with the sensitivity range of our eyes! Orbiting the supermassive black hole in the center of the milkyway galaxy, the sun burns blindingly bright at roughly 150 million kilometers from us, yet its impact on our tiny but magnificent photoreceptors is astounding. They both need to take the curtain call on this one!

Your origins, and of every single human being who is yet to live, or has lived, and every single life form that may be thriving on a second Earth millions of light years away, or of a fellow learner in another galaxy struggling for answers to deep questions on a land with many suns – they’re all connected through a common origin. Cast from a morsel of unimaginable inferno some three minutes after the big bang, your atoms have waited for over thirteen thousand million years to assemble on to a watery world, the flora and fauna of which has fed the entire lineage of your ancestors. Some have assembled into other strangely curious, but awesome creatures, others are placed high in the sky far from earth, some as stars and galaxies, others still waiting for their turn in the depths of colourful nebulae, and protoplanetary disks. To make matters worse for the hubris, your current assemblage comes with a frail and unconvincing warrantee. Eons after we pass away, our atoms and molecules will scatter back into the Earth, enriching the assembly line of new organisms, waiting for physical processes to announce their birth, ready for another round of the same.

Are we really a curious anomaly? Just four parts in a hundred of our genome separates us from our closest relatives on Earth, the chimpanzees. Yet, it is us that can create symphonies, art, technical masterpieces like the James Webb Space Telescope, invent mathematics and contemplate our place in the universe. Is 4% too much to ask for? The same differential might also be responsible for the smartest chimpanzees doing mundane tasks as their best demonstration of cognition or intelligence (as we define it, of course). Granted there is probably an inherent flaw in the way we portray our intelligence as a benchmark and project it on other organisms that do not stand a chance to fulfil the criteria of qualifying. However, think of the possibility of extending this small fraction of a difference in genome from us to an extraterrestrial life form; that it is 4% ahead of us in all that we do. Ask yourself again: is 4% too much to ask for? If not, then how far ahead would they be from us, just like we think we are from the chimps. Would they be interested in visiting us, talking to us? Would they be interested in our dreams, our stories, and our ambitions?

So far, we are on our own in an endless universe. Plodding on the regolith of Earth, we’ve gathered tools to access knowledge and wisdom and in its wake we’ve taken some good decisions, and many bad ones. As we contemplate our citizenship of earth and our future, our evolutionary relics remind us of a fragile relationship between life and death, physiology and teratology; the planet and deep space, the universe and us. Let us remind ourselves of who we are – a curious anomaly. The stuff that makes us up can be traced back to unimaginably hot cores of giant stars in space. The universe is both our cradle and grave. So, cherish, and celebrate the brief time you have on Earth while you continue to contemplate, articulate, explore, and morph through time.

Today and forever.